An Interview with Ronald van der Meijs

Sounda Architecture 01, Museum Bronbeek, Arnhem, the Netherlands, 2001. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

From fine handiwork to inflatable metaphors, drone-like sound systems to exquisite arboreal installations, Ronald van der Meijs work is based around responding to the natural world. Raised and educated in the Netherlands, the Dutch artist’s creations, which ranges from small-scale details to expansive land art projects, is, much like nature, complex yet intuitive. Often inspired by a simple idea or single hunch, van der Meijs’s finished works provide manifold possibilities for interpretation and reflection, providing a rich reflection on the natural world and our relation to it.

Sasha Amaya interviewed Ronald van der Meijs on how he builds and how he thinks about his work.

Sasha Amaya: Your practice is focused on the interaction of streamlined, elegantly designed objects and structures, yet their implementation—from sound and light to wind and vegetative growth and decay—explore a huge range of forces and scales. What drives your investigations, and how do you begin work on a project?

Ronald van der Meijs: The starting point is mostly sound. This will be generated by an installation which consists of both a technical or mechanical part and a natural part, which will direct the machines in various ways. Most of the time I focus on machine-like sculptures. But it is all derived from the location and its context. This can be the history of the place, the building itself, its function in the present and in history; often this theme is used by curators for their exhibition.

What drives my research is the space between desire and acceptance… this field is created by the natural elements, such as the wind, falling fruit, the growth and decay of nature, or physical systems like water evaporation, all of which I use for directing the work.

Sound Architecture 05, Hannah Peschar Sculpture Park, Ockley, Surrey, England, 2014. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: The notion of nature as an interlocutor is foundational to your work. Your works are generally not built to be placed in the landscape, to frame it, or contrast it, nor are they set up for people, to tell a story about them. Rather, your works often function, that is to say, become complete, when forces of nature react with them. In this way, your works are somewhat akin to those of a landscape architect or gardener: they grow on and come to blossom after you have left the scene. Has your work always been this way? How do you see the relationship between manufactured and natural object? Or the relationship between artist and nature?

RM: The relationship between manufactured and natural object is essential to my work. In order to study and use this space between desire and acceptance, I need nature. The essence of nature is that it has its own laws. It’s uncontrollable, uninspected, and not really reliable; [with the installations] it gives an unexpected reaction or sometimes doesn’t react at all. And the interesting thing is that, when things don’t react or generate sound like the audience is expecting it to, there is a strong will to do something about it—that’s what I mean about this space between acceptance and desire.

These days in our technocratic world we live a consumerist life where everything has to happen in a split second. It is a real entertainment earth. And of course we think that we can control everything, even nature itself. It’s an interesting development, I have to say, that although lots of people are unhappy with the life they live, they think to stop this by entertainment and consuming some stuff on the weekend. It doesn’t work.

Now to let people think about this behaviour I use uncontrollable natural elements. In seeing the sculptures as a type of technical machine they expect that it will work “properly”; however, it relies rather on the will of nature.

Sound Architecture 02, Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2003. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

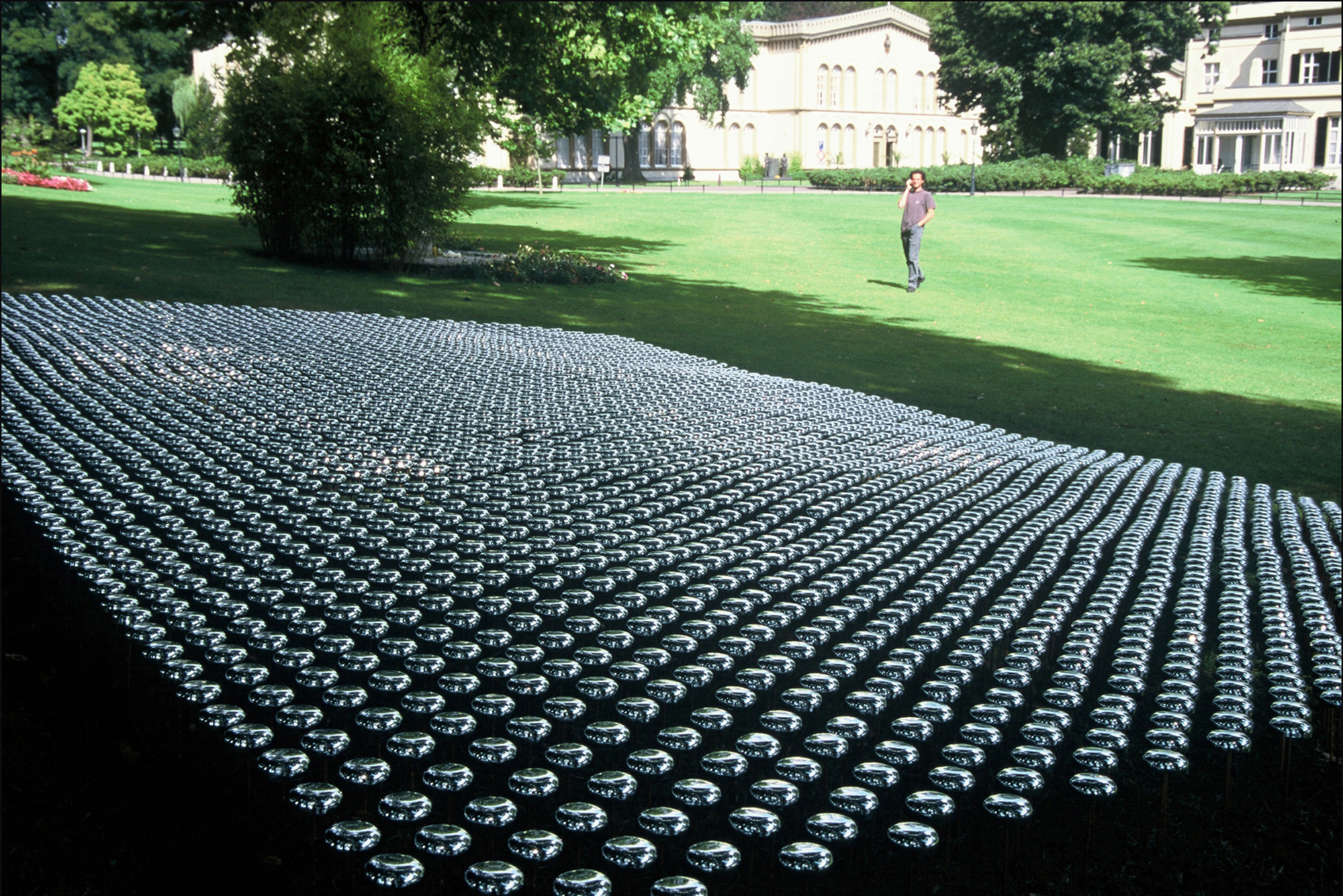

SA: You have done a number of works which fall into your ongoing Sound Architecture series: here you’ve installed chrome bicycle ball caps sloping over and along the ground near trees. In doing so, you’ve provided the possibility for sonic interaction between the tree and the things which fall from it, and your installation. What is the relationship between nature and culture—a relationship you say is important to you—in this work?

RM: In this work the two go hand in hand. Culture is the bicycle bell caps in many ways. Nature is the wind, the autumn, and the fruit itself which falls from the tree. Together it makes a full circle. The fruit grows high above the ground, it falls down and decays, providing food for the soil of the tree. Within this cycle I introduced a bell cap which translates vibrations of the falling fruit into a sound. One has to be very patient and lucky in order to see a fruit falling which generates a sound. But when this happens, it is a heavenly moment, don’t you think?

But I also speak of nature versus culture. In our lives and society almost everything is culture, or cultivated. Nature, the real nature, is a disturbing factor, which I like. It brings people back to the ground. Like a hurricane or tsunami or a sand storm. Or even a very dry and hot summer.

Nature versus Synthetics (Sound Architecture 03), Kunstfort Vijfuizen, Haarlem, Netherlands, 2007. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: How has this series—as an ongoing work—developed? How has investing in it repeatedly and in various locations changed how you re/create and view it?

RM: The very first time I did this installation was at Museum Bronbeek, which is the Dutch museum focused on old Knill soldiers fighting in the Indonesian-Dutch war. I made this bell cap installation in a strong and firm grid standing in very strict lines, like a bunch of soldiers, but after days of putting these bells into the soil I felt a victim of my own plan. It was hard to do and the repetition of five and a half thousand bell caps gets in your body and you start to become a little mad. It’s production work without any thinking whatsoever… So, in doing this kind of installation for the second time, I gave it a more natural form. I just started around a tree without measurements, by feeling. In this way it’s more interesting to make and it become part of the surrounding nature. Still, there is a typical handwriting of my own.

Cloud Sequencer, Into the Great Wide Open, Island of Vlieland, the Netherlands, 2017. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: Your Cloud Sequencer develops some of your previous work in environmental sound art. Can you tell us about how the Cloud Sequencer functions, how it was a development in your work for you, and how its specific location shapes its possibilities?

RM: It all started with a very small island in the north of the Netherlands. There was this village taken by the sea a couple of hundred years ago, in which lay a church. I was thinking about what a long while it must have taken before the church tower disappeared [under the sea], as well. I thought it was a nice visual, so to reference this old church, and the disappearance of the village, I used organ pipes.

The location for the installation was already known, a marvelous area of dunes. I thought to set the bass organ pipes so people could stand, walk or rest under the installation, waiting for changes in the sonic composition or for something to happen at all when it’s cloudy or there isn’t any sun. I wanted to use typical elements from nature to generate the sound of the organ pipes, but this was the first time that I used solar panels [for control, here the control of the air pump]. The pump varies in tempo when the sun shines; when a cloud comes over, it stops. The pitch is controlled by small nylon sails which are affixed to treetops, so when the wind starts to blow, they pull on the valves and pitch the sound of each pipe. Therefore, it is the clouds and the wind that are directing the sound composition.

Cloud Sequencer, Into the Great Wide Open, Island of Vlieland, the Netherlands, 2017. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: Visually, the Cloud Sequencer has a very spectral quality, reminding one of surveillance and drones. What kind of political and social undercurrents emerge in this work for you and for those who see it?

RM: None, in this case. It looks like drones, perhaps, but it was merely a design solution for the solar panel, the organ pipe, and the other parts to come together as a whole. It has more to do with island elements, the church, and the disappeared village in the dune surroundings.

A time capsule of life, Zone2Source Art Foundation, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2013. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: You have created a whole series of inflatable works, including A Time Capsule of Life and its 2.0 version, If I should live in the past I wouldn’t need a memory (and its 2.0 development) and Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty. Can you tell us a bit about these works and your interest in using plastic? What kind of forces trigger the inflation of these works?

RM: It started out with Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty. It was for a solo exhibition at a gallery in the shopping area of a metro station in the centre of Amsterdam. There were a lot of problems building the new metro line. The metro system is a sort of veinous system of the city as well, so I wanted refer to the medical procedure called “dottering” in Dutch, which refers to Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty, whereby a surgeon open up veins that aren’t functioning properly.

[For A Time Capsule of Life,] I used special hardware store shopping bags, which both crackle when you touch them, and also refer to the shopping and consumerism in that area, to construct the tube structure. These kinds of structures have a short lifespan because of the delicate material. I like that because it refers to living things, which also die. By sealing these bags into small balloon elements and then sealing them together as a tube structure a [larger, connected] inflatable structure is produced. Every element has its own air tube system.

A time capsule of life, Zone2Source Art Foundation, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2013. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

By pumping this structure one generates a meditative crackling sound, [reminiscent] of something growing. By connecting a lot of contact microphones to these plastic structures and electrical components and sending these sounds to a mixing deck, I can make a composition of all these sounds hiding in these structures. Normally an audience is not patient enough to listen to the crackling noises of these structures, but when I do a sound performance which is amplified enormously, people are really stunned.

For the 2013 solo A Time Capsule of Life, I referred to the structure of a tree seed, which spreads by wind, and because of the arboretum character of the park. The plastic bag has a lot of similarities with a seed capsule, too. They both carry goods or food for a living. So by introducing a vacuum pump I could now inflate and deflate, which gave me the opportunity to express this idea of growth and decay, and to produce a more intense sound. Here, for the first time, my interest in growth and decay as both very beautiful things was born. The two belong to each other but are also very different from one another.

Parthenocarp, Kunsteyssen Art Foundation, Alkmaar, the Netherlands, 2010. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: Craftsmanship is a defining quality of your artistic practice. How has your craft, and the importance it holds in your practice, changed over your years as an artist? How have you developed yourself as an artist and as a craftsperson?

RM: Wow, that’s a long story! To make it short [laughs] I now try to make all things Wabi Sabi, with the least effort possible and a maximum of expression. Yes, I try to make nice material combinations and I search for the proper dimensions and compositions of the parts and materials. But I don’t sandpaper things away anymore; it’s the scars that I like, and all the marks made during the production which have to be there.

Another important factor is that I make all my works now like a sculptor does. No drawing, no scale models, just start and let it grow. The best work comes out of this! I never know beforehand how it will end up, which is the nicest way to create something. Also there is more space to experiment with this way of creating.

So, in short, I am kicking away my perfectionist habits. That is just maniacal behaviour, and it is strange that people like to see shiny, perfect, smooth things: for what? Okay, functional objects have to be smooth in order to fulfill their purposes, I admit. But my machine sculptures need to have a soul. And that is only possible when you don’t polish everything away and let it grow in a natural and slow way. That said, this only applies to work I can make on my own: when other people are involved, like assistants, one needs to have a design. Otherwise, it’s not possible to get things done, and sometimes there can be a lot of money involved, too.

Exploring earthly sounds for nine candles, De Vishal Art Foundation, Haarlem, the Netherlands, 2017. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: Many of your works, and your best known works, are either at large scale, or assemblages of small objects in vast quantities, yet you write that you do not use drawings and models only to create larger objects, but oftentimes create smaller models of large objects, or, sometimes after a large-scale project, work in small scale for a time. What does this large-to-small scale conversion, and working in small scale more generally, add to your practice? Are there any small studies about which you’re particularly pleased or excited?

RM: I did make a lot of study models and I love them all. But I prefer not to make models anymore. The only thing I still need to do is make models or one-to-one tests of new mechanical ideas. I need to know up front if an idea is technically possible. And I test a lot of 3D ideas with sketches, too. I make fast drawings on anything I can find; sometimes I’m sorry that I don’t do this properly on nice paper, just for selling them more easily [later]. But I can’t. If I’m busy with these works I can only concentrate on the machine sculpture itself and not on a nice drawing.

Play it one more time for me / La Ville Fumee, Art Foundation De Fabriek, Eindhoven, the Netherlands, 2013. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

SA: You attended the Land Art Biennial Mongolia in 2018. What are some of the things happening in land art around the world right now which fascinate you?

RM: It’s not so traditional anymore. Anything can happen—just like indoors! The only thing is that you have to take the weather conditions into account, and sometimes the vandals who like to demolish art.

SA: How do you see yourself as an advocate for art, for land art, and for the environment? What concerns occupy you? How do you understand land art as addressing some of concerns we currently face environmentally and culturally, locally and globally?

RM: It will change when we see the necessity… but it’s difficult. You cannot order a third world country to stop polluting or to stop cutting the forests because we already made a mess out of it 200 years ago. That is very arrogant. But we can try to set a positive example for others to come.

I hope we learn to be satisfied with less, much less! That’s a key factor I believe. People are too greedy, wanting more and more and spending energy impulsively on rubbish, or cars designed anew every six months. We have to think properly about what we really need and what we just want to have. There isn’t enough for that. By the way, you have to work a lot for all that stuff, people forget that. We should work half the time we do now and do more creative things, travel, learn from other cultures. Don’t watch TV all the time because it’s fake. Care more. Sometimes do nothing at all and reflect upon that. That does make one happier!

A Nomadic Diptych, Land Art Biennial Mongolia, Murun Sum / Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2018. Image courtesy of Ronald van der Meijs.

To learn more about the work of Ronald van der Meijs, click here.